New AGA exhibits go big or go home

It’s a busy day over at the Art Gallery of Alberta, where a pair of exhibits open that offer us both a global and a local perspective on society. The AGA has put together a couple of short blurbs outlining the shows quite ably:

It’s a busy day over at the Art Gallery of Alberta, where a pair of exhibits open that offer us both a global and a local perspective on society. The AGA has put together a couple of short blurbs outlining the shows quite ably:

19th Century French Photographs

Paris. Jan. 6, 1839. The first public announcement of a new invention for making pictures appeared in the press. The daguerreotype, named after its inventor, J.L.M. Daguerre, consisted of an image of an amalgam of mercury particles on a silvered copper plate made with an artist’s camera obscura. Three weeks later, the London press announced W.H.F. Talbot’s photographic process involving a paper negative from which a positive could be made. Thus was realized the ageold dream of “Nature painting her own portrait.”

Within two decades, Daguerre’s process had become obsolete, whereas Talbot’s invention became the basis for photography as we know it today. By 1847, the Frenchman Louis Blanquart-Evrard had improved Talbot’s process, making it commercially viable. Drawn from the National Gallery’s extensive collection of nineteenth-century French photographs, the exhibition consists of daguerreotypes, salted paper, albumen silver and photogravure prints made by some of the major practitioners working in France at the time, including work by Eugène Atget, Edouard Baldus, Maxime Du Camp, J.B. Greene, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, F.J. Moulin, Nadar, Auguste Salzmann, and Félix Teynard among others.

Nowhere else in the world were so many trained artists testing the scope of the new invention as in France . They explored such subjects as landscape, architecture, portraiture, archaeology, street activities, war, and studies of the nude. The exhibition traces their paths of exploration, ending with the work of Atget. Although his career as a photographer began in the late 1880s and continued until his death in 1927, his twentieth-century work may be seen as a continuation of the nineteenth-century photographer’s concerns. And yet he is an artist whose vision has inspired many photographers of our own time.

This exhibition will feature 66 photographs from the first decade of French photography to 1900 as well as several twentieth-century examples of Atget’s work.

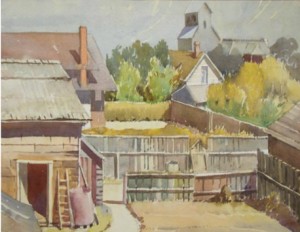

Prairie Life: Settlement & the Last Best West 1930-1955

At the turn of the 20th century the Canadian frontier was framed as a place for opportunity; a place of natural abundance that could be the foundation for a utopian society, or a blank slate where the individual could carve out their own destiny. The promised land.

The strength of this vision was irrevocably altered, however, with the massive impoverishment and dislocation brought about by the Great Depression and the Second World War.

This exhibition traces 25 years on the Canadian prairies, from the “Dirty Thirties” to the middle of the 1950s, when the idea of the Canadian west went through a period of significant change. The vision of the west as a promised land has its roots in the 19th century and played a critical role in the rapid settlement of Manitoba , Saskatchewan and Alberta . The Great Depression marked a turning point in this vision and the beginning of a shift from a primarily rural to a primarily urban population. The role of the farm in both the region and the nation would never hold the same dominant position. By the end of this period Alberta ’s fortunes lay in oil, not in agriculture.

Though the 1930s saw unprecedented economic hardship, it also was a time of positive change within the visual arts. Fine art schools, artist societies and museums were becoming well established. The National Gallery of Canada circulated more and more exhibitions throughout the region and there were new levels of investment in arts education. Artists engaging with modernism produced images newly attuned to everyday life. A more democratic engagement with themes, however, was coupled with an investment in the nature of painting itself. Artists emphasized visual strategies over a literal interpretation of their subject matter.

This exhibition features images of settlement on the prairies during a time when the Canadian frontier was undergoing irreversible change. Modernist artists such as Maxwell Bates, Fritz Brandter, Janet Mitchell, Bartley Robilliard Pragnell, John Snow and Ella May Walker interpreted the changing rural and urban landscape. Without nostalgia, they depict both abandoned and working farms, small towns and growing cities. The resulting works contrast anxiety with optimism, desolation with industriousness and decay with growth. Drawing from the Art Gallery of Alberta’s permanent collection, this exhibition features artists who were central to the history of modernism in this region.