TAG! YOU’RE IT! Fear and Loathing at the Anti Graffiti Symposium

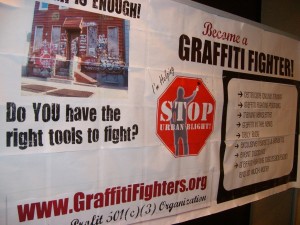

Outside the meeting rooms at the Westin Hotel where the Anti Graffiti Symposium (TAGS) was held in Edmonton this past week, two large canvases were set up and a box with spray paint and colourful markers was placed beside them.

Outside the meeting rooms at the Westin Hotel where the Anti Graffiti Symposium (TAGS) was held in Edmonton this past week, two large canvases were set up and a box with spray paint and colourful markers was placed beside them.

Over the course of the two-day conference, the delegates, many of whom were police officers from across North America, were invited to decorate the canvases with their own graffiti. Shy at first, they eventually took to the idea, and by the time the event wrapped up, there was some interesting art work on display.

It wasn’t graffiti culture’s only appearance at the symposium. At a session called “A Tagger’s Perspective,” Calgary-based graffiti artist Daniel J. Kirk stood at a podium in a room full of delegates whose jobs involve eradicating graffiti, and said things many of them didn’t want to hear.

“Our cities have become fairly bland. We’ve pushed this 1970s modern aesthetic that’s grey and dull and boring,” said Kirk, a University of Calgary fine arts graduate, as he defended graffiti. “Graffiti does inspire people,” he noted.

Capital City Cleanup, the agency which oversees the city’s graffiti

management program, hosted the symposium in conduction with the city’s Community Standards Branch and the Edmonton Police Service. Sharon Chapman of Capital City Cleanup, who has attended TAGS conferences in other cities in previous years, says more alternative voices are being brought in each year. She says the more there are, the less “us and them” it feels and the more opportunities there are to find solutions.

“Capital City Cleanup is accused of trying to whitewash Edmonton and that clearly isn’t the case,” explains Chapman, who is the agency’s graffiti project manager. “We want to balance it between property owners who don’t want vandalism to their property and people who want to see artwork. Nobody is going to be successful unless we find this common ground.”

Many of the sessions at the symposium had titles with enforcement themes such as “Investigative Solutions” or “Graffiti Vandals: You Can Make Them Pay.” One session titled “Penmanship of a Vandal” even offered insight on using graffiti style comparisons as evidence for obtaining convictions.

But sandwiched in between were other sessions, like the taggers’ forum, which stretched beyond the idea that all graffiti was bad. “Graffiti in the Modern World: Pop Culture, Politics and Public Art,” was delivered by Kristy Trinier of the Edmonton Arts Council, and youth from iHuman were invited to another session perform theatre scenes explaining why some of them were drawn to graffiti. Trinier, during her presentation on public art, told delegates there is a difference between “graffiti vandalism” and “graffiti art,” and that painted-over art is an embarrassment. She said other countries like those in South America have a lot of murals, and that it isn’t as difficult for an artist to get permission to make one. She said that means graffiti doesn’t stand out so much when it appears. Trinier also pointed out that in New York and London, once-illegal pieces of graffiti art have been embraced by neighbourhoods and are now protected. A prominent example includes Keith Haring’s “Crack is Wack” mural, which is now a tourist attraction in Manhattan.

“I hate to break it to you, but a lot of people think graffiti is really

cool. Capital Health uses graffiti style writing in a campaign to get the attention of children,” Trinier told delegates. “It’s on Louis Vuitton bags.”

The alternative messages weren’t always well received. Trinier was challenged by a delegate who said that while it may be art, people aren’t particularly thrilled when it shows up on their property.

The taggers were also challenged. A police officer from Coquitlam, B.C. stepped to the microphone and accused panel members of hypocrisy for espousing ideals of anarchy. He noted that anarchy requires everyone having a say, but he said the graffiti artists didn’t give anyone a say when they left their marks.

The taggers were also challenged. A police officer from Coquitlam, B.C. stepped to the microphone and accused panel members of hypocrisy for espousing ideals of anarchy. He noted that anarchy requires everyone having a say, but he said the graffiti artists didn’t give anyone a say when they left their marks.

“There’s no solution in just trying to control everything,” Kirk answered.

At one point the officer asked the panelist, some of whom are now professional artists who do commissioned work, when was the last time they painted without permission. A murmur went through the crowd and there was a pause while everyone

waited for the answer.

“Probably, like, three weeks ago,” replied Scott Chan, an abstract painter who lives in Vancouver. You could almost hear the gnashing of teeth.

Chapman says no one can deny that graffiti can have artistic merit, but in some cases the artists are expressing alienation or anger. Allowing such expression is important, she says, but she also says it’s good for a community to deal with the underlying social problems that make people feel angry or alienated. Public murals, which have community support, are one way she says people feel can feel connected to a community. Restorative justice programs, where taggers meet community members whose property they vandalized, is another.

Despite the disagreement at the TAGS symposium, both sides are at least talking to each other.

“The more we work together, like at the conference, the more we can hopefully find a solution,” Chapman says. “It’s not a black and white answer.”