ARCHITECTURE: Douglas Cardinal vs. the soulless city of glass

Architect Douglas Cardinal has always sought to incorporate both history and natural surroundings into his designs, which range from the Telus World of Science here in Edmonton and the Museum of Civilization in Ottawa, to the Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC.

Architect Douglas Cardinal has always sought to incorporate both history and natural surroundings into his designs, which range from the Telus World of Science here in Edmonton and the Museum of Civilization in Ottawa, to the Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC.

So how will the Calgary-born, award-winning aboriginal designer be received when he speaks to a full house this Thursday, March 29 at the Art Gallery of Alberta about promoting indigenous design in this city – where, let’s be honest, we seem allergic to our own past?

Most of us would flunk even a basic quiz on aboriginal history in Edmonton. Our celebration of the gold rush, Klondike Days, was re-branded as Capital EX. And how many Edmontonians know that the giant smokestack surrounded by empty fields along the northeast LRT line was once home to Canada Packers? Who knows that the neighbourhoods around it were called Packingtown, and that the city’s meat plants were what defined this city in the first half of the 20th Century before oil started squirting out of Leduc #1?

Our history is relegated to Fort Edmonton Park where we visit it once every few summers.

Cardinal (right, and his Stony Plain residence, above), whose sold out appearance is part of a series of presentations by a group called Media Art and Design Exposed (MADE), has told interviewers and audiences that he has rejected some elements of the past as part of his style. Old design templates from Europe, he explains, seemed out of place here so he felt the need to create new ones.

Cardinal (right, and his Stony Plain residence, above), whose sold out appearance is part of a series of presentations by a group called Media Art and Design Exposed (MADE), has told interviewers and audiences that he has rejected some elements of the past as part of his style. Old design templates from Europe, he explains, seemed out of place here so he felt the need to create new ones.

“The Group of Seven created their own style and it grew out of the Canadian landscape, and the dramatic colours, forms, textures, etcetera,” Cardinal said in an interview with University of Calgary radio station CJSW earlier this month. “So, I felt why not develop an architecture that’s related to the land forms of the Americas and the traditions of the Americas? The Greeks developed their architecture around their landscape, or the Egyptians. Any culture usually develops their structural forms, their building forms, from their environment.”

Cardinal’s style tends to incorporate a lot of curves – a more natural form than the angles of past building styles. He says some of it has been influenced by everything from the Rocky Mountains and the foothills, to the hoodoos at Drumheller. He’s also a proponent of achieving consensus among all the players in his projects, ranging from his design of a Cree village in Quebec that’s been recognized by UNESCO, to the design of the aboriginal museum in DC.

When he began work on the design for the Washington project (left), he says he gathered elders from all over the Americas, and they passed around an eagle feather as they gathered everyone’s ideas. He noted that when he first looked at the site, he realized there had once been a creek there, and they decided to incorporate that as part of their design.

When he began work on the design for the Washington project (left), he says he gathered elders from all over the Americas, and they passed around an eagle feather as they gathered everyone’s ideas. He noted that when he first looked at the site, he realized there had once been a creek there, and they decided to incorporate that as part of their design.

It may sound touchy-feely, but his firm has always been on the cutting edge of technology and was among the first to fully embrace computers. Cardinal once said in a lecture to the Inter-American Development Bank in 1997 that his technological savvy sometimes helped ease the concerns of potential clients who worried about hiring an “Indian.”

But what if rejecting our past and creating a new story is part of who we are as Edmontonians? Perhaps we enjoy razing our former selves and carving new personas out of the bald prairie, a direct result of being the descendents of people who left somewhere else to start their new lives.

Canadian artist and novelist Douglas Coupland, in his second novel, “Shampoo Planet,” has a narrator who revels in a sterile Los Angeles hotel room after spending a summer backpacking in Europe. The narrator, Tyler, found Europe’s history to be stifling and will soon be returning to his choice of study in community college – in hotel management. He says, “I like hotels because in a hotel room you have no history, you only have essence. You feel like you’re all potential, waiting to be re-written like a crisp, blank sheet of 8½ by 11-inch bond paper. There is no past.”

Canadian artist and novelist Douglas Coupland, in his second novel, “Shampoo Planet,” has a narrator who revels in a sterile Los Angeles hotel room after spending a summer backpacking in Europe. The narrator, Tyler, found Europe’s history to be stifling and will soon be returning to his choice of study in community college – in hotel management. He says, “I like hotels because in a hotel room you have no history, you only have essence. You feel like you’re all potential, waiting to be re-written like a crisp, blank sheet of 8½ by 11-inch bond paper. There is no past.”

In Coupland’s non-fiction book about his own hometown, “Vancouver, City of Glass,” he celebrates the fact that the city has little history compared to others in North America. He says Vancouverites find the city’s “lack of lack of historical luggage liberating.”

But the idea that the land we inhabit has no history is an invention. Zoe Todd, a local Metis whose blog posts and photos about the lack of recognition of aboriginal history in the area were the original spark for MADE’s speaking series, says guilt over troubling questions over land ownership could explain Edmonton’s failure to recognize its original inhabitants. She also says that every successive boom in Edmonton brings a rush of development, and each time it happens, utility trumps history.

“We celebrate the oil industry but not so well on everything else,” says Todd. “The boom and bust cycle is just so total. It puts us on autopilot.”

Nadir Bellahmer, chair of MADE, says he hopes people who come to Cardinal’s lecture, possibly designers and planners themselves, will come away inspired to include more aboriginal themes in their projects. Bellahmer says he has relatives who visit the city from Algeria and France ask to see indigenous culture expressed here. He calls Edmonton’s aboriginal population an “untapped resource” of culture that visitors are interested in seeing.

“All of the glass skyscrapers aren’t going to put Edmonton on the map. I think if Edmonton is going to position itself as a unique place, we’re going to have to have something different,” Bellahmer says. “It’s important to recognize our narrative as culture becomes global. Could there be a Seattle sound or a Halifax sound like there was with music scenes in the 1990s?,” he asks.

“All of the glass skyscrapers aren’t going to put Edmonton on the map. I think if Edmonton is going to position itself as a unique place, we’re going to have to have something different,” Bellahmer says. “It’s important to recognize our narrative as culture becomes global. Could there be a Seattle sound or a Halifax sound like there was with music scenes in the 1990s?,” he asks.

Todd, meanwhile, raises the common notion that it’s important to be aware of history in order to prevent past mistakes. She also says have a need for meaning in their lives, and history can be a tool for that. Coupland even acknowledges a danger in completely lacking a personal narrative. His essay in his book “Polaroids of the Dead” about Brentwood, the well-heeled Los Angeles suburb that became infamous for murder of Nicole Brown-Simpson and the arrest of O.J. Simpson in 1994, speaks of a process he calls de-narration. The de-narrated inhabitants of Brentwood, Coupland says, re-invent themselves with gym workouts and plastic surgery in the hopes of getting an acting gig, which he says will instantly give them a new narrative. He says Brentwood doesn’t even exist as a legal entity, and “its entire paper archives fit snugly inside a cardboard Kinko’s box inside a librarian’s Buick Le Sabre trunk. Brentwood is a place that has never thought of itself as even existing. That is part of its charm, its attraction,” Coupland wrote.

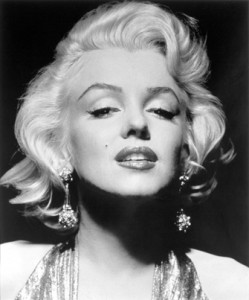

Yet his essay notes that Marilyn Monroe killed herself there. Her fame, Coupland informs us, was unable to provide her with a narrative. Her home, with its 50s-stye lamps, Mexicana furniture and suitcase hi-fi, seemed “anonymous and hotel-like, places were Monroe had lived much of her life. In the end it seemed she was trying too hard to put a pleasant façade onto – nothingness,” Coupland wrote.

Without a narrative, or a history, her life lost meaning.