ART: Talent overcomes cultural supression in Alex Janvier at the AGA

The superb collection of some 90 artworks making up the Alex Janvier exhibit at the Art Gallery of Alberta touches on many levels.

The superb collection of some 90 artworks making up the Alex Janvier exhibit at the Art Gallery of Alberta touches on many levels.

Primarily abstractionist, Janvier’s colourful, curvilinear assemblies inspired by traditional themes are well represented at the AGA, from their exploratory beginnings in the 1960s through the ‘70s when they became his most familiar style. Most Edmontonians should be familiar with his fresco mural “Circle of Life” in the central atrium of the Muttart Conservatory.

As rich as the visual impact of the Alex Janvier exhibition is, the story of his life provides even greater depth. In a media preview May 17, the Northern Alberta Dene artist explained that the source of many of the images stem from his childhood, which along with his language, is all that remain from a culture that was systematically destroyed. He retains and nurtures that culture with his uses of the floral patterns, decorative motifs, spiritual symbols and colour arrangements in his abstract compositions, but they come from another time and tradition that has been lost.

“I saw the last of the real beading and the basket weaving and the porcupine quill working,” Janvier says. “I saw those old people, the old, old ladies doing it.”

In little more than a single generation, traditional knowledge was almost eradicated from his culture. Janvier speaks poignantly about colourful yarns being balled into tassels that were used to decorate jackets and dog and horse harnesses ― especially at Christmas. But then, when he was eight years old, he was taken from his family and put in the Blue Quills Residential School near St. Paul for almost a decade.

“When we came back, a lot of those old people had passed away,” he says, “There was nobody to pass their knowledge on to because we had been put into the schools. There was a big gap between us who came back and our grandparents. We were told they were evil. They made you mistrust your own grandparents.”

The poisonous effect of the aboriginal schools continued through the efforts of the bureaucrats in the national “Indian Affairs” department that controlled native life. Up until the 1960s, First Nations members were not even allowed to leave their reserves without permission from the appointed “Indian Agent.”

Fortunately, Janvier’s talent was recognized at an early age. Two never-before-seen examples painted for a mural and begun when he was 15 years old demonstrate the talent that prompted the school’s headmaster to put him in touch with the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Extension. Instructor Karl Altenberg is credited with providing early instruction. Janvier then pursued his talents at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology, where he was the only First Nations student taking fine art, which upset the Indian Affairs bureaucrats when they discovered he wasn’t pursuing a trade. Instructors Marion Nicoll and Illingworth Kerr spoke for him and Janvier stayed to graduate with honours in 1960.

Fortunately, Janvier’s talent was recognized at an early age. Two never-before-seen examples painted for a mural and begun when he was 15 years old demonstrate the talent that prompted the school’s headmaster to put him in touch with the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Extension. Instructor Karl Altenberg is credited with providing early instruction. Janvier then pursued his talents at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology, where he was the only First Nations student taking fine art, which upset the Indian Affairs bureaucrats when they discovered he wasn’t pursuing a trade. Instructors Marion Nicoll and Illingworth Kerr spoke for him and Janvier stayed to graduate with honours in 1960.

Works in the AGA exhibition from the ‘50s and early ‘60s demonstrate a sophistication and a knowledge of European art – particularly of Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee of the Blue Rider group. But even in those works, Janvier uses those approaches to depict his own cultural and traditional explorations.

As he developed, his struggles with the Indian Affairs bureaucracy continued. In the early ‘60s, he began incorporating his treaty number “287” as part of his signature, which he continued until the late ‘70s. Conflicts ensued. Janvier was hired in 1965 to sit on an Aboriginal advisory committee preparing the “Indians of Canada Pavilion” for EXPO ’67 but was fired the next year for being – rebellious. The Pavilion was pretty much the first attempt to bring aboriginal Canadian artists together, and many of them had issues to address, discrimination and cultural suppression not the least. Janvier was one of five commissioned artists to paint nine-foot, round wall installations for the Pavilion. The pieces, some controversial, were destroyed with the demolition of the facility, but even before, his work “The Unpredictable East” was relegated to a rear location and re-titled “The Beaver Crossing Indian Colours.” No trace or images of the mural remain.

A series of examples at the AGA also represent his period as a founding member of the Aboriginal Group of Seven, which exhibited for several years in the ‘70s. The group also became known as the Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporation (PNIAI), which included Bill Reid as a some-time eighth member.

AGA curator Catherine Crowston has incorporated works from that period and later that are also a departure from Janvier’s most well-known approach.

“One of the challenges of the show is that I didn’t want to just show classic ‘70s works, I wanted to include works on through the ‘90s,” she says. “I wanted to give the viewer a sense of Alex’s range and it’s important to show his diversity.”

She does that by concluding the exhibition with contemporary “abstracted” portraits painted within the past two years of all the Group of Eight members. The last work as one travels clock-wise around the room is a self-portrait.

In the 1960s, Janvier found a kindred spirit in architect Douglas Cardinal, who also happens to be First Nations.

“That was the first time someone understood what I was doing,” Janvier says. “I was painting, but it wasn’t the traditional native painting. It was what you see here today. I was out of key with the horse and buggy subject matter and he was also a step away from the world of architecture and the way most of the buildings look.”

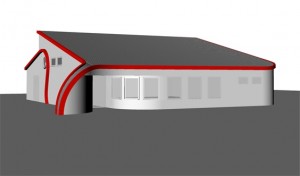

These men have remained in touch with their cultures and have created their respective bodies of work to international acclaim. Janvier has been awarded the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts and, like Cardinal, is a member of the Order of Canada. Both men are still active. Cardinal recently designed a 3,000 square foot gallery near Cold Lake for Janvier that is nearing completion (architect rendering, right).

These men have remained in touch with their cultures and have created their respective bodies of work to international acclaim. Janvier has been awarded the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts and, like Cardinal, is a member of the Order of Canada. Both men are still active. Cardinal recently designed a 3,000 square foot gallery near Cold Lake for Janvier that is nearing completion (architect rendering, right).

The Alex Janvier exhibit will be on display until August 19.

(Photos by Stuart Adams)