Rock photographer Ethan Russell remembers: What was it really like in the ’60s?

Evidence is mounting that the 1960s was indeed the best decade for rock ‘n’ roll.

Evidence is mounting that the 1960s was indeed the best decade for rock ‘n’ roll.

Given how often we hear it, this has got to be more than just the Baby Boomer conceit that because something was important to them, it should be important to everyone else – forever. Sure, there was that pesky Cold War, and Vietnam, and Nixon, but there was also the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who and other iconic bands that had the freedom to develop rock ‘n’ roll into a true art form before it turned into a business.

That’s the word from photographer, filmmaker and writer Ethan Russell, who remembers the ‘60s even though he was there – plus there’s ample photographic evidence to back him up. He went on tour with the Rolling Stones, photographed the Beatles’ famous rooftop concert, shot the cover of the Who’s Quadrophenia, and we could go on and on, with almost magical access to the hottest artists of the day.

“The ‘60s were a combination of having the best time you ever had in your life and having it be about something,” Russell says. “And that opportunity doesn’t really exist easily anymore.” There are a number of reasons for this, partly due the fact that EVERYBODY is making records these days, but even that, in the end, has to be a good thing.

“The ‘60s were a combination of having the best time you ever had in your life and having it be about something,” Russell says. “And that opportunity doesn’t really exist easily anymore.” There are a number of reasons for this, partly due the fact that EVERYBODY is making records these days, but even that, in the end, has to be a good thing.

The San Francisco photographer will be telling his unlikely story – being the virtual “eye” that witnessed the birth (and afterbirth) of rock ‘n’ roll as we know it today – at Festival Place Saturday night, touring to promote his third book, An American Story. Where so many have failed so miserably in the past, he says, Russell will try to describe “what it was really like.”

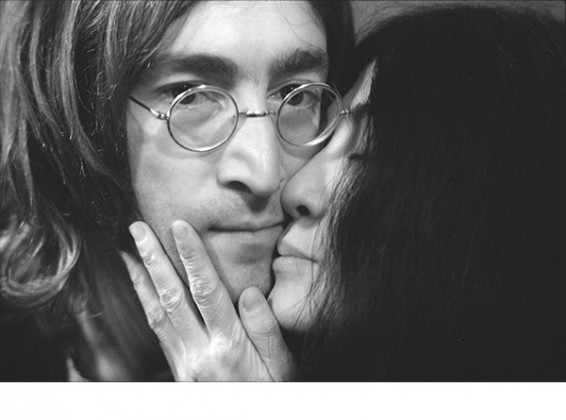

This story is more unlikely when you consider that this passionate fan, for whom “music was everything,” had no formal training in photography, but was imbued with a natural gift for the art form that landed him some big jobs early on. That he happened to look like John Lennon helped him get in good with the actual John Lennon, he says, but there was more to it than that. He remembers a photo shoot in London:

“I was nice to his girlfriend,” Russell says. “When I met him Yoko was just coming on the scene, people didn’t know who she was. I was just so enamoured of the entire event. I wasn’t really a photographer, so when we got done doing the first session and the interview at the flat in London we went to EMI and Yoko was there. I didn’t know who she was. I just took pictures of her because John was talking to her. And they were beautiful pictures. The ones of Yoko I thought were better than the ones with John. He loved them. I thought I’d blown the session with John, so I phoned him up – how did I get that number? – and he said, ‘Come on over, we’ll shoot again.’ That I didn’t have any negative energy about me at all helped.”

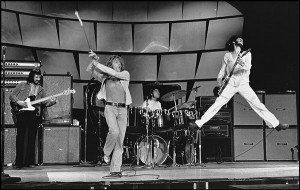

In another “Almost Famous” sort of scenario, though Russell wasn’t too much younger than his subjects, Mick Jagger also took a shine to the hot young photographer who loved rock ‘n’ roll and never had anything bad to say about anybody. Russell was hired as the official tour photographer for the Rolling Stones American tour in 1969. That, he says, is the most fun he’s had at work – “and it’s always work.”

In another “Almost Famous” sort of scenario, though Russell wasn’t too much younger than his subjects, Mick Jagger also took a shine to the hot young photographer who loved rock ‘n’ roll and never had anything bad to say about anybody. Russell was hired as the official tour photographer for the Rolling Stones American tour in 1969. That, he says, is the most fun he’s had at work – “and it’s always work.”

His subsequent resume reads like the roster for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame: Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Eric Clapton, Jerry Lee Lewis, you name the icon. The only one missing is Russell’s biggest hero Bob Dylan – the epitome of the singer-songwriters who had the greatest impact on Russell’s youth – and Dylan hates having his picture taken.

Frankly, Russell doesn’t blame him.

“There are few things more deadly in life than a photo session,” he says. “It’s a completely abstract experience that nobody involved with it could reasonably like. When you say you’re having your picture taken, what is that? When people are engaged in doing in some other thing, being on the road, recording a record, or any other thing that is taking their attention, then what you get is a real moment, but if what you’re doing is setting up a picture, it’s an entirely different mindset. It took me years to be comfortable with it. Unless the photo session is truly a photo session in a studio where it’s very clearly the job of the photographer to make something happen, then you find a middle ground walking around trying to take pictures, and they’re really the worst … having your picture taken is a completely bogus experience.”

Russell says it took him years to come to this realization consciously, and only then after embarking on the third phase of his unusual career, what he considers the hardest art form of all short of actually making music: Writing. As he puts it, “Having to explain it really forced me to think about what I was doing.”

Asked if the fact that EVERYONE can not only make a record, but take a photograph (or make a film) has “cheapened” the art of photography, he says he’d prefer a more positive word: “It’s changed.” He and millions of other people got the first inkling of the new paradigm with radio back in the ‘60s, when you realized that you and John Lennon might be listening to the same Chuck Berry recording from the opposite ends of the Earth. It’s like that now – times a trillion.

Asked if the fact that EVERYONE can not only make a record, but take a photograph (or make a film) has “cheapened” the art of photography, he says he’d prefer a more positive word: “It’s changed.” He and millions of other people got the first inkling of the new paradigm with radio back in the ‘60s, when you realized that you and John Lennon might be listening to the same Chuck Berry recording from the opposite ends of the Earth. It’s like that now – times a trillion.

Russell explains, “The biggest change at a deep level is that analog is what humans are made of, and digital is what we do synaptically. And there’s a real difference. It’s true in music and it’s true in photography. That everyone can do it, so instantaneously to communicate almost subconsciously, it turns it into something that looks to me more like language, and that’s what I think is really going on.”

He promises he won’t get getting so deep during his one-hour presentation, at least not until the Q&A session that follows, and says, “The night at Festival Place is the first time I’ve really tried to describe what it was like, trying to describe what I did, because it was so unlikely.”

Like the entire ‘60s itself, apparently. There hasn’t been a time quite like it since, even if you weren’t there to remember it.