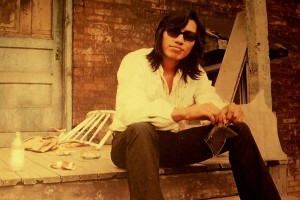

OSCAR FILM: Searching for Sugar Man about art for art’s sake

Posted on February 25, 2013 By Derek Owen Entertainment, entertainment, Film, Front Slider, tv and radio

Imagine you wrote and recorded a couple albums only to find them with $1.99 tags in the delete bin at the old A&B Sound a couple weeks later. Now imagine finding out 20 years later that you were bigger than Elvis Presley in some country on the other side of the world.

Imagine you wrote and recorded a couple albums only to find them with $1.99 tags in the delete bin at the old A&B Sound a couple weeks later. Now imagine finding out 20 years later that you were bigger than Elvis Presley in some country on the other side of the world.

It’s hard to wrap your head around the remarkable story of Detroit musician Sixto Diaz Rodriguez, the son of a Mexican immigrant worker whose anti-Apartheid protest songs touched an entire generation of South Africans – especially his best known song, “Sugar Man.” Because the albums were bootlegs, and because the music industry is full of shysters, Rodriguez never saw a cent of royalties and continued to live in relative poverty.

Winner of best documentary at the recent Academy Awards, “Searching for Sugar Man” screens Tuesday, Feb. 26 at the Metro Cinema.

Swedish director Malik Bendjelloul cuts between shots of urban decay in post-recession 2008 Detroit with Rodriguez’s gorgeous music, the lush string arrangements, brooding voice, and elegiac lyrics. From there, the story switches to Cape Town, South Africa, where record store owner Stephen Segerman, together with a South African journalist and countless members of the South African music scene, gush endlessly on the scope and popularity Rodriguez’s songs, spliced with segments of apartheid protests from the 1970s. Interview subjects mince no words when they say that this music was a very bright light in the era of almost universal artistic censorship.

The story of how Rodriguez’s music came to South Africa is too whimsical to be dismissed as myth. Former Motown Records head Clarence Avant had signed Rodriguez to his Sussex Records label in 1970 and recorded two albums, which, in the testimony produced by legendary producer Steve Rowland, was stronger material than anything Bob Dylan did to that point. However, not much came of it in the U.S. An American girl brought one of Rodriguez’s records to South Africa, the story goes, played it for friends, who all loved it – and Rodriguez’s work soon became widespread there in the same way Metallica got popular in America. Minus all the money, of course.

The filmmakers managed to locate Avant, who comes off like a music industry heel in one segment. The record executive gushes that Rodriguez was one of the top five most talented performers he had worked with, which included the likes of Michael Jackson and Diana Ross, but his demeanour shifts dramatically when asked what happened to the money owed to Rodriguez for all the South African record sales (numbering around 500,000 albums). Avant rapidly goes on the offensive, attacking the interviewer and offering a short, virulent but rhetorically limp defense by saying it doesn’t matter anymore where the money went.

The filmmakers managed to locate Avant, who comes off like a music industry heel in one segment. The record executive gushes that Rodriguez was one of the top five most talented performers he had worked with, which included the likes of Michael Jackson and Diana Ross, but his demeanour shifts dramatically when asked what happened to the money owed to Rodriguez for all the South African record sales (numbering around 500,000 albums). Avant rapidly goes on the offensive, attacking the interviewer and offering a short, virulent but rhetorically limp defense by saying it doesn’t matter anymore where the money went.

That this story could not have happened in the computer age is driven home by two South African fans’ search in 1996 for the obscure musician via the Internet and email, which were relatively new inventions at the time. Rodriguez was eventually tracked down at his home in Detroit two years later, where he had been found to have spent the previous 28 years living a rather prosaic life, raising children, working in a blue collar job, unaware of his fame in South Africa. The man was just not meant to have his name in lights – at least not yet. The film details a series of sold out shows Rodriguez did in March 1998 around South Africa – sold out arenas, people of all ages singing his songs with the fervour of U2 fans. It’s nothing short of shocking considering his complete obscurity in the USA.

The film’s overarching concept of art of art’s sake is played to the hilt, and does not seem disingenuous as Rodriguez becomes more well known. He and his family speak with a complete absence of pretension in a manner typical of the working class. He wrote his music not to make millions of dollars or be famous, but to simply express himself and say things he thought were meaningful. Rodriguez comes off not as a musical martyr, but as the quintessentially pure “artist.”

History appears to have vindicated Sixto Rodriguez, a true everyman who did more than his share of honest artistic work, despite his new-found success. And with the aid of technology to help spread ideas and information, hopefully the future will grant artists like Rodriguez a kinder fate than what he bore for 28 years – as an unknown and un-experienced success.