EIFF REVIEW: Spinning Plates feeds heart and soul

Posted on October 2, 2013 By Jeremy Loome entertainment, Entertainment, Film, Food, Front Slider

Towards the very end of Joseph Levy’s acclaimed documentary Spinning Plates, airing Oct. 3 as part of the Edmonton International Film Festival, there is a defining moment. World-renowned chef Grant Achatz compares his ultra-expensive, ultra-exclusive Chicago restaurant to those hometown spots run by his parents when he was a kid. He says, “It’s the same thing. It’s the same; you’re at the same time making people feel comfortable and exposed, and that’s a restaurant.”

Towards the very end of Joseph Levy’s acclaimed documentary Spinning Plates, airing Oct. 3 as part of the Edmonton International Film Festival, there is a defining moment. World-renowned chef Grant Achatz compares his ultra-expensive, ultra-exclusive Chicago restaurant to those hometown spots run by his parents when he was a kid. He says, “It’s the same thing. It’s the same; you’re at the same time making people feel comfortable and exposed, and that’s a restaurant.”

It’s important because it’s horribly inaccurate; but it demonstrates ably how someone can be elitist, exclusive, and detached – and great at what they do – yet still delude themselves into thinking themselves the same as everyday folks.

Grant Achatz’ restaurants have as much in common with mom-and-pop greasy spoons as a guy hitting used buckets of balls at a public driving range has with a legacy membership at Augusta National. Achatz is a master of great flavors and obsessive drive, not human nature. And it’s this flaw, a flaw as grand as any the rest of us might bear, that helps make Levy’s film a great story.

A great story always says something profound about the human condition, and helps us recognize something about ourselves that we need to know more about, a part that needs to be exposed whether it’s good for us or not.

In a film about restaurants, that great truth is that we face two choices in life: to focus on ourselves, or to focus on our community. It is rare that we straddle both successfully. Levy touches on this balance with rare deftness, never heavy-handed or preachy, allowing three families’ stories to unfold in with eye-opening insight. It doesn’t hurt that the cinematography is at times gorgeous, also rare for a film about restaurants.

Spinning Plates is also a film about relationships: there are few actual discussions of food during the film’s 90-odd minutes. Instead, Levy focuses on why running a restaurant is important to people in each of three cases: Achatz’s world-renowned Chicago eatery Alinea, which specializes in unique molecular gastronomy; a seven-generation-owned restaurant in rural Idaho, Breitbachs; and a small Mexican startup in Tucson called Gabby’s.

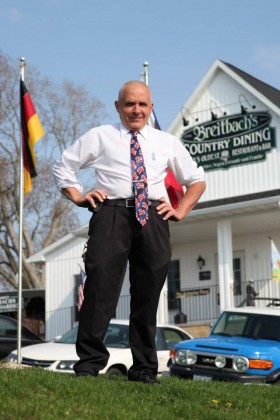

In the case of Breitbach’s, it was also important to a fairly large swath of the rural Midwest, apparently – they’ve helped rebuild it after devastating fires twice, donating thousands of hours, dollars and gifts of materials. The patriarch, Mike, is the defacto local volunteer-about-town, mom bakes the pies and six of their kids work at the place which, though situated in a town of just 70 people, can attract as many as 2,000 loyal patrons from the larger surrounding region on a busy weekend.

In the case of Breitbach’s, it was also important to a fairly large swath of the rural Midwest, apparently – they’ve helped rebuild it after devastating fires twice, donating thousands of hours, dollars and gifts of materials. The patriarch, Mike, is the defacto local volunteer-about-town, mom bakes the pies and six of their kids work at the place which, though situated in a town of just 70 people, can attract as many as 2,000 loyal patrons from the larger surrounding region on a busy weekend.

Gabby’s is the struggling outlet of the three, a Mexican place started on love and a loan against a mortgage. You never get the sense it’s much more than an obsession on the part of its owners to make something that will improve their daughter’s life; it’s perhaps the saddest story of the three, even though it illustrates the great love one can find in a close-knit family.

And then there is Achatz, an artistic pioneer in gastronomy whose landmark restaurant has won three Michelin stars, the pinnacle of food endorsement globally, on two separate occasions.

As the money and community-driven tribulations of Gabby’s and Breitbachs demonstrate their need to embrace their friends and family for support, Achatz is lost instead in his great obsession: to be considered the greatest of his time, to be remembered long after he is gone, to have his restaurant considered a cultural landmark that shifts how people think about food. For reasons we’ll later learn, he turns not to family for validation, but to the wider world of a specialty, cooking.

“A hundred years from now, will people say ‘did you ever hear of Alinea?’,” he muses, in a moment rife with narcissistic delusion and passion in equal doses, his hope not only that he’ll be remembered, but that it will be prompted by the positive end result of people finding new ways to appreciate cooking. It’s an individual, selfish goal; it’s about achieving greatness via a singular vision and potentially immortality. Behind every great obsessive drive is a need to win, to prove yourelf dominant because, dammit, that way you don’t have to rely on anyone else. You don’t need the group’s approval, you lead the group. You don’t need the group’s strength to survive, you can do it on your own.

Achaz comes from a broken home. We later learn his father ran a “rinky dink” small-town restaurant, derided “presentation” cooking, mocked his son’s culinary aspirations and, despite an otherwise normal family life at first, eventually abandoned his wife and son. So his son rejected small-town life, rejected normal cooking to the point where he refuses to even make it, and admits his goal of creating art on every plate and every palate is “absurd” in its complexity and originality.

And its cost: a single-bite dish can take up to twelve hours and a team of six to complete, and his restaurants are so exclusive, obtaining a reservation can cost $5,000 at auction.

It’s not about money, because it’s not about supporting his larger family. It’s about social elevation. He had a break with his most important community – his own family – at an early age and it toughened him up and made him independent, an overachiever. But it also refocused him towards finding his validation not in the warmth of family, which he has but whom we barely meet, but in gaining critical approval and besting his mentor, “crushing him” like someone will come along “and crush me” in a few years, he says.

It’s not about money, because it’s not about supporting his larger family. It’s about social elevation. He had a break with his most important community – his own family – at an early age and it toughened him up and made him independent, an overachiever. But it also refocused him towards finding his validation not in the warmth of family, which he has but whom we barely meet, but in gaining critical approval and besting his mentor, “crushing him” like someone will come along “and crush me” in a few years, he says.

When Achatz is fighting cancer and his wife complains that he continues to only sleep fours hours a night and work sixteen hour days to ensure the restaurant’s quality is maintained, despite his doctor saying it could kill him by causing remission, he admits she’s right. He also admits it’s selfish to his family who would lose their father and provider. “I can’t say no you’re not right, because she is right, but the opportunity is too great. It’s going to help me attain my life fantasies my ultimate goals or going to kill me. But I don’t have a choice,” he says.

People from broken homes? They lose a piece of their sense of security. They often replace it with individual accomplishment and the routines of obsessive behavior. That’s one of the truths demonstrated in Levy’s exceptional doc, the dualistic nature of mankind, of us and them, of self and community, of yin and yang, of achieving and dominating versus sharing and accepting. At Breitbachs, even though the family seems to work 24/7 and hundreds of customers consider it a community centre, everyone has a sense of togetherness, the strength of numbers. Achatz makes his own security, setting a standard and challenging others to best it. Meanwhile, Gabby and Francisco Martinez are literally losing house and home, starting from nothing and going back to it in short order.

In illuminating these choices and where they leave these three families, Levy’s film shows rare insight into the human condition, without laying out any sort of staid recipe. It’s a movie about the food of life, not just the type we wolf back gratefully. It addresses disparity, and social acceptance, poverty and wealth, loss and rebirth. It’s a film with bite.