Opera by night, criminal justice by day, drama all the time

Posted on October 23, 2013 By Mike Ross Entertainment, Front Slider, Music

Opera singer Bertrand Malo has such a challenging day job – Crown Prosecutor – that it’s tempting to ask if listening to the gory details of horrific crimes is a good way to unwind from the stresses of opera.

Opera singer Bertrand Malo has such a challenging day job – Crown Prosecutor – that it’s tempting to ask if listening to the gory details of horrific crimes is a good way to unwind from the stresses of opera.

He answers with a laugh, “Yes, I need both. Opera is a great world. However it’s really difficult to make a living. Being a lawyer provides me the comfort and security. However, when you go back home after you spend a day in court dealing with those horrible things on a daily basis, opera is a good stress relief.”

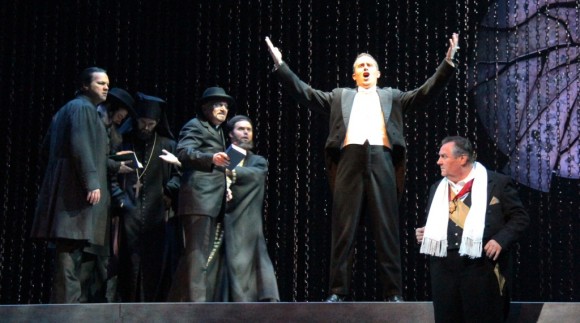

And yet opera is usually filled with horrible and gory things, too, death, heartbreak or both. Salome, being produced by Edmonton Opera at the Jubilee Auditorium Oct. 26, 29 and 31, is a particular bloodbath. Based on the story of the Biblical figure and the man who spurned her love, John the Baptist – victim of the most famous decapitation in history – the opera is taken from a play by Oscar Wilde, set to the music of Richard Strauss and filled with the sort of gritty human drama Malo sees in court all the time. He’s playing a supporting role – as “Nazarene No. 1” – as the bass-baritone has in a number of other Edmonton Opera shows. He’s on the board, too.

Malo says, “Salome is about decadence, about family dysfunction, and there’s lot of violence and blood, child abuse and awful, awful, awful parents.”

In real life, in a real courtroom, “I’ve prosecuted impaired drivers, sex assaults, robberies, homicides, so I’ve seen pretty much everything. That’s why I can make a link between opera and my work. People do things and it has consequences. I deal with the victims as well as the criminals. And opera is definitely about drama and the consequences of what people do.”

Painting by Andrea Solario (circa 1506)

There are other parallels between vocation and avocation. The McGill University-trained singer, who practices opera singing an hour a day much in the same way people work out at the gym, is in a sense required to perform in court with the same passion as he would on an opera stage. He has to be convincing. People’s lives hang in the balance as lawyers speak in front of the judge, the victims, the public, the media, sometimes a jury, and in the Court of the Queen’s Bench, they even have to don ceremonial robes. No froofy wigs. Canada doesn’t go that far.

This production of Salome is toying with anachronism by setting the Biblical tale in the era that the opera premiered, in 1905; it caused a stir at the time for the famous “dance of the seven veils” where the very idea of a woman ending up naked at the end of it (even if she obviously wouldn’t have been in those days) ruffled the feathers of respectable citizens. It was even banned for a time.

The time and setting aren’t as important as the core message, Malo says, “It’s about decadence and society. Whether it’s 2,000 years ago, 100 years ago or today, these stories are still quite relevant if you look at our society, how we consume, how we act without caring for others or the environment. We’re so busy consuming we don’t consider the consequences.”

At least we don’t cut people’s heads off much these days.

Malo says, “Or you’d end up in my court.”