JOYCE SMITH: No leavin’ on her mind

Posted on May 27, 2014 By Mike Ross Entertainment, Front Slider, Music, music

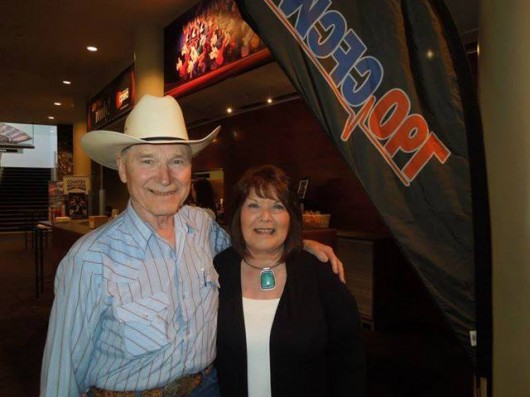

If the life of Joyce Smith is a country song, it’s a happy one. No heartbreak. No cheatin’. No hurtin’. She’s still married to the same rodeo cowboy who stole her heart more than 52 years ago.

If the life of Joyce Smith is a country song, it’s a happy one. No heartbreak. No cheatin’. No hurtin’. She’s still married to the same rodeo cowboy who stole her heart more than 52 years ago.

Her one small regret is not fulfilling a childhood dream to be a country superstar in Nashville.

“I regretted it a lot, that I didn’t get down there and do something – until my kids were born, and then it didn’t matter,” she says. “I’m happy with what I did. I’m in the Canadian Country Music Hall of Fame. I played the Grand Ole Opry. And I still love to work and I work a lot. I love it. It’s just in my blood.”

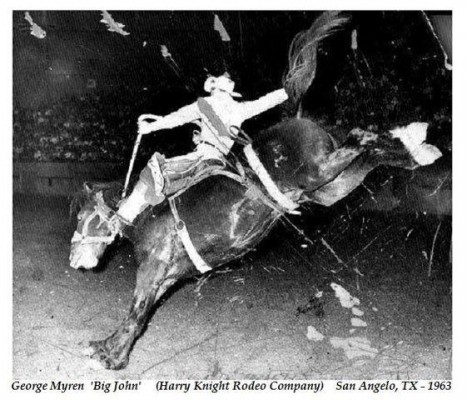

Joyce Smith has been singing country music for around 60 years now, much of that time with her husband George Myren, former Canadian champion bronco rider who still plays bass in her band, Rodeo Wind. The good old boys back up some Canadian Country Music Legends Friday June 6 at the Beverly Heights Community League. This is hardcore traditional country much closer to Hank Williams than, say, Luke Bryan. The event is sponsored by the Olde Towne Beverly Historical Society – fitting since the headliners Smith, along with Alfie Myhre, Bev Monro, Randy Hollar and Pete Hicks would’ve all been singing country music when the town of Beverly was absorbed by Edmonton in 1961. Old coal mining town.

Around that same time, Smith did go to Nashville – a path taken by countless young Alberta country singers since, with varying degrees of success.

Webb Pierce

Smith got her first taste of fame in Edmonton during the oil boom 1950s thanks to 630 CHED – she still sounds out the call letters as “C-H-E-D” – which had a weekly Opry-style radio show called the Jubilee Jamboree. She became an unpaid regular on the show at the age of 14. Performers weren’t paid because they had to audition for a spot on stage each week, and so were considered contestants. Smith never missed a single episode. Five years later, she turned pro, joined the union and got hired as the singer in the Rodgers Brothers Band, which opened for honky tonk star Webb Pierce at the Edmonton Gardens in 1960 or thereabouts. He liked Smith so much that he boldly announced to the crowd he intended to “take her to Nashville!”

This was news to her.

“I just about fell on the floor,” Smith says. “And then he said, ‘I’m going to call her out to do another song.’ I thought, what am I going to do, what am I going to do?! And I thought: Jambalaya, Hank Williams, that’s the first thing that came to mind.”

The crowd loved it, by all reports, and so did Webb Pierce.

A seasoned performer by then, still a teenager, Smith had heard this “I’ll make you a star” line from big hats before, but Pierce actually followed through. After the gig, the musicians gathered at a friend’s house for a few drinks. Webb phoned his producer Owen Bradley at his home in Nashville at 3 a.m. to enthuse over his new Edmonton discovery. Smith still remembers hearing Bradley’s braying drawl over the phone, “Well, Webb, if you think she’s good enough …”

A week later, Smith got the call and flew on her own dime (with help from her parents) to Nashville to cut a record with one of country music’s most famous producers, the man behind some of Patsy Cline’s classic songs, including “Crazy” and “I Fall to Pieces.”

Smith never fancied herself a songwriter; but neither was Cline, one of Smith’s main role models for women of country music among not too many (then, as now). Bradley chose for Smith a tear-jerker written by Webb Pierce and Decca Records staff songwriter Wayne Walker called “(If You’ve Got) Leavin’ on Your Mind,” expressing the sort of heartbreak Smith had never experienced: “If you got leavin’ on your mind. Tell me now, get it over. Hurt me now, get it over.”

The Jordanaires

No expense was spared in the studio: They hired the Jordanaires, which backed up Elvis Presley, members of the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, and all the hottest session cats. Smith signed a contract with Decca, and with noted artist manager Jim Denny, who had run the Grand Old Opry at the Ryman Auditorium and was famous for telling Elvis he ought to stick to driving trucks.

Patsy Cline herself puts a wrinkle into this. The story goes that she was in Owen Bradley’s office one day, heard the record Smith made, and immediately wanted the song for herself. According to Smith, “He said, ‘no you can’t have it. I’m going to to see what that Canadian gal does with it.’” Cline apparently said pretty please with sugar on top, but Bradley and the label wouldn’t back down. Smith’s single, released in 1962, didn’t crack the top-40, but sold more than 100,000 copies, a major hit for a first record and enough that the Canadian gal recouped the considerable studio expenses and actually made a little money in royalties. Patsy Cline wound up recording the song and releasing it in 1963. It didn’t make the hit parade, either. It was her last single before she died in a plane crash in March of that year.

Smith met Patsy Cline just once, backstage at a gig in Edmonton, but never had any contact after that. On the idea that her hero also recorded Leavin’ On Your Mind, Smith didn’t feel thwarted. She was thrilled, “I thought, wow, Patsy Cline is doing my song! Not that I wrote it, but it was still my song.” There is a good case to be made that selecting and interpreting a great song is as much a creative process as writing one. Ella Fitzgerald didn’t write her own material, either.

Looking back with 20-20 hindsight, this would’ve been the perfect moment for Smith to go as hard as possible, move away from Edmonton, make more records, form a band, go on tour, sacrifice everything to make it big – but she blinked.

“I came back home,” she says. “They didn’t know what the single was going to do, and after it started to take off, they phoned and said, ‘you should move to Nashville and maybe we could find you some jobs,’ and it was a maybe, and I was 20 years old and a little bit worried about going to Nashville on my own and trying to find a job, so I didn’t go.”

She had six months of a record contract to complete, recorded a few more singles, but they didn’t go anywhere. To make matters worse, Jim Denny, who had been behind her all the way, died of cancer a few months later and the business was taken over by his son, who “didn’t have the guts that Jim did,” Smith says. The son wasn’t even aware Smith had a management contract with him.

So back to Edmonton she came – to be with George. They’d met over a few drinks after a rained out rodeo in St. Paul, Alberta, where she was playing with the Rodgers Brothers. They married in 1962, and after the Decca deal was done toured rodeos together around North America, Smith picking up whatever gigs she could and working under the table. She never got close to getting that big chance again.

So back to Edmonton she came – to be with George. They’d met over a few drinks after a rained out rodeo in St. Paul, Alberta, where she was playing with the Rodgers Brothers. They married in 1962, and after the Decca deal was done toured rodeos together around North America, Smith picking up whatever gigs she could and working under the table. She never got close to getting that big chance again.

But they enjoyed a thriving music career in Alberta. The couple settled in Edmonton in 1964, had their first kid two years later and have had steady work ever since. Smith has toured the world, released six albums and has to be one of the longest continuously working musicians in Edmonton. She was inducted into the Canadian Country Music Hall of Honour in 2010.

We can’t let the happy country song end without finding out what a traditional country singer thinks of new country, as if we couldn’t guess. Smith says, “I don’t think today’s country music is really what we called country music. There are some things: Alan Jackson does country music, Mark Chesnutt does country music, but some of these young people, I listen to girl singers and I can’t tell one from the other. Same with the guys. And I’m in the business. I do listen to the radio and I do try to keep up with the young people are doing.”

No regrets anymore, though. On the notion that Smith actually blew her big chance not because she was afraid, but because of true love, she says, “I’m an old country girl. I believe in honouring things.”

Sounds like a line in another happy country song.

Tickets to The Canadian Country Music Legends show on June 6 are $40 and not available online; call Cornel at 780.413.6244 or in person at the Beverly Business Association, 4014 118 Avenue, during business hours.