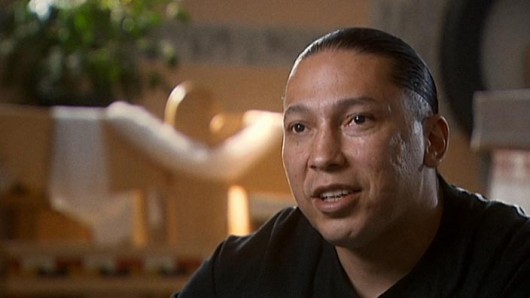

INTERVIEW: The Unstoppable Shawn Bernard

Posted on October 14, 2014 By Mike Ross Crime, Culture, Entertainment, Front Slider, life, Life, Music, News

Shawn Bernard survived losing both of his parents and his sister to drug overdoses. He survived poverty, living on streets, becoming a drug dealer, gang leader and drug addict himself. He survived jail.

Shawn Bernard survived losing both of his parents and his sister to drug overdoses. He survived poverty, living on streets, becoming a drug dealer, gang leader and drug addict himself. He survived jail.

In an inspirational story he’s told to youngsters across Canada countless times since, he prevailed over all these trials to break the cycle of abuse, drugs and alcoholism to become a proper father to his children, a respected rap artist named Feenix and an aboriginal community leader – only to have his life devastated six months ago because he gave a ride to the wrong people.

Bernard is now a quadriplegic, the victim of a stabbing on April 25, 2014 that left him paralyzed from the chest down. Doctors struggled to save his life. He’ll never walk again and has only limited use of his arms and hands. He can operate a motorized wheelchair and text with his thumbs.

Bernard, 41, leaves out no gory details during a recent interview at the Glenrose Hospital, with his wife Shelley and 10-year-old son Blaze sitting beside him. Dad is awaiting placement in a long term care facility – though they’d much rather have a home that could accommodate his needs. Income from his performances and public speaking have dried up, so fundraising efforts are underway to help the family, including a GoFundMe campaign. Of his six kids (from four different women), Bernard says, “It’s so tough for them to see their idol, their dad, the strength of everything I was doing for them, to all of the sudden this happening.”

His attacker is in jail awaiting trial for attempted murder. Pride from the streets shows through when he says, “I never thought anybody would do this. I had my guard down. I never thought anybody had the balls to do this to me.”

After all he’s been through, Bernard ponders, “I always try to think why. Is this karma for my past life of hurting people? I hurt a lot of people when I was on the streets. Every talk I would do for kids, I would talk about karma. You never know when it will come back on you. I thought what I was doing in the community was my way of making up for it. But I feel like I let the devil into my vehicle when I let those drunk people in the car. I didn’t even know they had an open bottle of vodka. And I was stabbed. The blade went into my spine. There’s still hunk of metal in my neck right now that they don’t want to bother because they’re scared it might go further and do more damage.”

Bernard’s physical body may be frail, but his words still hold power, perhaps even more than before, as he works to include most challenging chapter of his life into his inspirational story. Bernard has been asked to give talks to native kids again, and though he doesn’t have the muscle control to shout like he used to, recently performed at the recent Aboriginal People’s Choice Music Awards (APCMAs) in Winnipeg, a dream come true, yet bittersweet.

“I’d never been asked to perform before,” says the three-time Canadian Aboriginal Music Awards winner. “And now I got asked to perform this year, and I’m like, you know I’m in a wheelchair, right? And they said that’s fine. Anything to make you comfortable. It was a goal of mine to perform there, so I said, OK, I’ll do it this time. I did it in my wheelchair.”

The response was tremendous. “The feedback was so large,” he says. “So many people were saying how inspired they were, making comments. It made me tear up to read a lot of those comments. I’m glad I could help in some way, to inspire people, to motivate people that are down.”

Gang of rappers

From the 2007 NFB documentary Walking Alone

To say Bernard had a tough childhood is an understatement. His mother died of a drug overdose when he was four years old; and at 17, he lost his father the same way. He says he doesn’t remember a time when drugs and alcohol weren’t around him. His family rented a house on Boyle Street, for a short time. “There were parties all the time,” he says. They moved a lot. He and his sister Chrissy went to a different school every year, sometimes the only native kids in class, sometimes not. They had to fight for respect.

“We went through a lot of racism and a lot of fistfights to protect ourselves, and then down the road because of the fighting ended up becoming the toughest kids in school,” he says. “And then I became a bully.”

Bernard became addicted to drugs and alcohol before he was even a teenager, doing break-and-enters and other crimes to feed his habits. He and his friends were put into juvenile detention – and that’s where their musical ambitions were awakened. Bernard wrote his first song in jail and helped form a native rap group that ended up becoming a gang. Inspired by artists like Public Enemy expressing the voice of the underclass in America, Bernard and his friends started rapping about their lives in Alberta.

“For me and my friends, we were on the streets, living street life, into crime, going in and out of jail. We never knew how to get beats or how to record. The first thing we started writing about was pride, all native pride. Everything was about pride. We had these dreams about being the first native rap group to make it to MTV, and MuchMusic. We had all these visions of wearing chokers and braids and having a microphone in one hand and a tomahawk in the other, that kind of thing.”

The only thing that was ever recorded during that time was a cassette tape made by a friend who’d heard the rappers at parties and wanted to get a demo to music business people. Unfortunately, on the way to deliver it, “We got into some trouble,” Bernard says, and the only copy of the tape was lost.

While some first nations people were made to feel ashamed for being native, “On the street with all our friends, they thought it was cool,” Bernard goes on. “But as we progressed as criminals, we kept going in and out of jail. Every time we were in jail we had these positive visions of what we were going to do when we got out. But we’d fall back in the same cycle, drugs, alcohol and crime to support our drug and alcohol habits, and then we’d go back to jail. When we were on the streets we got into drug dealing, and we started enforcing our drug dealing. People had to buy off us, and we could control where they would sell their drugs, and we had our territory and we became known as a gang, and when we became known as a gang, we started writing songs that focused on drugs and violence.”

NFB throws a lifeline

Bernard’s lowest point came in 2006. He was arrested and charged with aggravated assault and break and enter with intent to cause bodily harm, and locked up in the Edmonton Remand Centre. “There was a stabbing incident. It was pretty well a home invasion. Just a drunken, drug-dealing kind of thing,” he says. “The crown prosecutor told my lawyer that if I pleaded guilty right away they’ll give me seven years, and I said no, I’m taking this to trial. And the crown prosecutor got mad and he told my lawyer to tell me that I can’t even count on both hands what they’re going to ask for if I get found guilty.”

Bernard’s lowest point came in 2006. He was arrested and charged with aggravated assault and break and enter with intent to cause bodily harm, and locked up in the Edmonton Remand Centre. “There was a stabbing incident. It was pretty well a home invasion. Just a drunken, drug-dealing kind of thing,” he says. “The crown prosecutor told my lawyer that if I pleaded guilty right away they’ll give me seven years, and I said no, I’m taking this to trial. And the crown prosecutor got mad and he told my lawyer to tell me that I can’t even count on both hands what they’re going to ask for if I get found guilty.”

His kids, meanwhile, had been taken into foster care. He phoned their mother (not his current wife) – who was struggling with substance abuse herself – and begged her to hold off signing the children over to the province permanently until his bail hearing 30 days down the line.

Two days later, he was told his sister Chrissy died of a drug overdose.

There was nothing to do but go back to his cell.

“I prayed and prayed and prayed to the Creator to give me one more chance, to let me out at this bail hearing that I will change my life and get these guys out of foster care and I will change my life and quit drug dealing and all that, and try to be a better man. Be a father.”

Some of his relatives and friends had an elder do a pipe ceremony at the bail hearing. Bernard fasted, and prayed. When the judge delayed his decision for two weeks, he felt like giving up, “But I thought, no, this is just a test just to see how true I am to my prayers, to see if I’m going to give up. Because everybody was offering me everything, drugs, on the unit. So I waited two weeks and I fasted again, and every guy on the unit said I wasn’t going to get out. My lawyer said I won’t get out for under 10 grand, but I told everybody I was getting out. When it was all said and done the judge gave me a $500 no-cash bail. I didn’t have to pay a cent. I got out, and I went straight to look for him …” – at this point he puts his arm around Blaze, who’s been sitting through the interview the entire time – “and his older brother Shawn and told them they were going to come home and live with me.”

Bernard focused on turning his life around. He stayed sober, maintained a stable home with his wife, found work, started studying towards an Aboriginal Community Support Worker diploma (which he earned in 2008), and resumed his music. He sat in at local rap shows wherever he could and started writing what would become his debut EP, The Real OG – OG stands for “original gangsta.” It contained positive songs like Quit Blackin’ (as in blacking out from getting drunk), but the language was still very much of the streets. At this time Bernard vowed to stop using profanity in his lyrics.

“I was listening to it with my kids in the car,” he says. “I just caught myself and said, you know what? I don’t want my kids to think this is cool. And if I don’t think my kids should be listening to it, why should I think other kids should be listening to it? So I started doing positive messages. I tried to inspire, and motivate, and most of my songs are about dreams, and wishing and hoping, things like that.”

While still free on bail awaiting trial, he had a friend help him with a grant application to the Alberta Foundation for the Arts to record his music. As his story attracted media attention, the National Film Board made an offer to make a documentary about him. Walking Alone came out in 2007 – and it worked wonders at Bernard’s sentencing.

“I ended up pleading to a lesser charge,” he says. “When I went to court, it was funny. It was historical. We had my documentary set up in the courtroom with all the screens, one in front of the judge, so everybody was watching the documentary at my trial. All the community people were there from all the agencies, the elder, they were all there to support me. There were a lot of people in my corner, with all the good things I was doing in my community, I went back to school, got my kids out of child welfare, so after seeing the documentary, they offered me to plead to a lesser charge, so I pleaded to a lesser charge and I received three and a half years of house arrest.”

The NFB documentary also introduced Bernard to the APCMAs for the first time. They invited him along to Winnipeg in late 2007 to help promote the film.

“I never even knew it existed,” he says. “I went and I saw all the acts, the rap groups, all the rockers and I was just in awe of everything because I didn’t know there was such a thing as the aboriginal music awards, all these native people dressed up fancy. While I was there I looked up on stage, and I said, that’s going to be you going for an award next year, Shawn.”

This also came to pass. When he arrived back home, there was a letter in his mailbox from the AFA saying he got the grant. He recorded a few songs, sent in a home-burned CD in at the last minute and wound up being nominated for an Canadian Aboriginal Music Award the following year. Though he didn’t win that time, Feenix finally earned three trophies, mainly on the strength of his 2009 song Strong, which has become an anthem for Alberta’s native community. He raps, “I’m strong, I’m strong like two people, ‘cause I live in two worlds I choose equal, one world has to do with the past, the other is a world that’s moving too fast.”

Bernard doesn’t want to name the native gang he helped create, which is said to still have chapters across Canada. It’s not necessarily because he’s ashamed of his past, but because “I’m still friends with a lot of those people, I’ve still got a lot of love for them,” he says. “They respect me for turning my life around and doing what I set out to do with my dreams and goals in music. They respect me for trying to help kids. It’s not like I’m trying to get people to drop out or whatever. I don’t want to support it, and I don’t want to disrespect it, either way. What I do is try to talk to kids and try to catch them before they make that choice, and just let them know what happens when they make their choices because I’ve been through it.”

Since his injury, Feenix has risen with a new song: “I’m still here, still livin’ a life, even though they tried to take my life with a knife. I fought to stay alive, now I’m livin’ to fight and I’m still fightin’ to live for six kids and a wife …”

He says it’s a work in progress.