The strangE CASe of LeE HARVeY OsMOND

Posted on October 29, 2015 By Mike Ross Entertainment, Front Slider, Music, music, Visual Arts

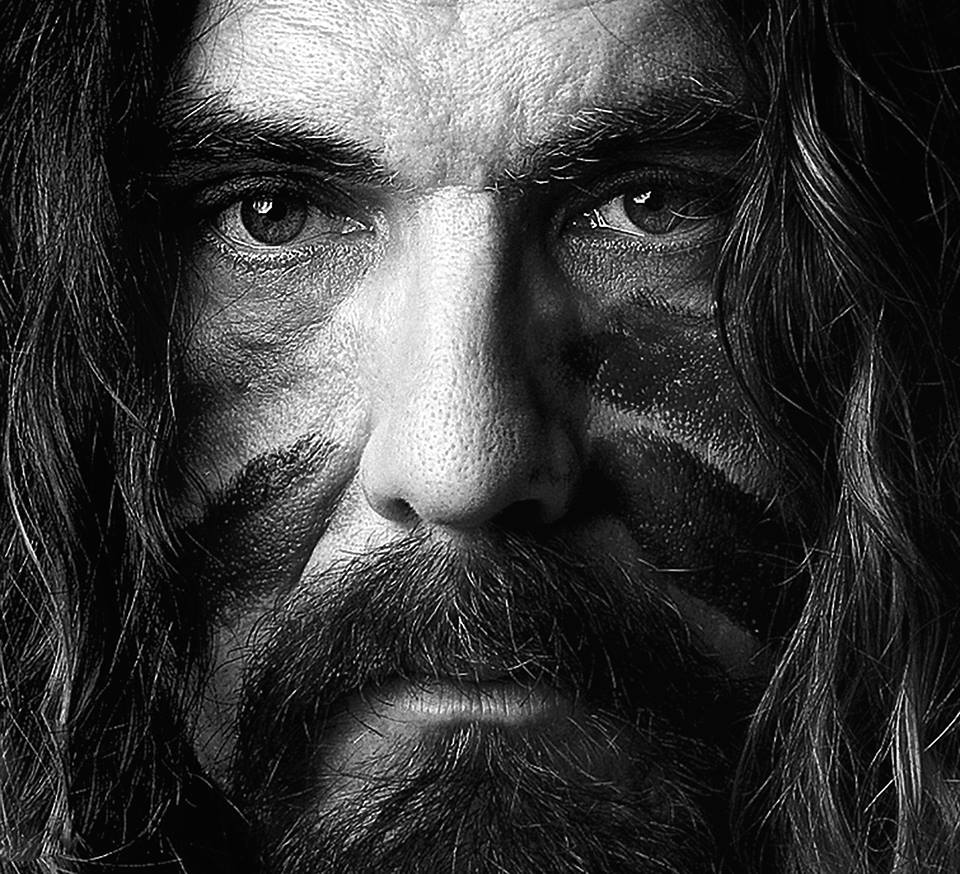

If you believe that there is no such thing as a random event and that every seemingly insignificant decision can have a profound impact on the very fabric of the universe – or at least the destiny of a rock musician – then consider the story of LeE HARVeY OsMOND in this latest episode of WHO NAMED THE BAND.

If you believe that there is no such thing as a random event and that every seemingly insignificant decision can have a profound impact on the very fabric of the universe – or at least the destiny of a rock musician – then consider the story of LeE HARVeY OsMOND in this latest episode of WHO NAMED THE BAND.

They play Thursday, Nov. 5 at Festival Place.

The odd casing of the band name “is just some bullshit,” says singer Tom Wilson. After a brief discussion on the cosmic interconnectedness of all things, he adds, “I just think it looks good. Look at my paintings. They’ve got a lot of stuff I get asked about, too. I do a lot of writing, I write stream of consciousness on giant canvases. People ask why I do it, and it’s because it looks good.”

The odd casing of the band name “is just some bullshit,” says singer Tom Wilson. After a brief discussion on the cosmic interconnectedness of all things, he adds, “I just think it looks good. Look at my paintings. They’ve got a lot of stuff I get asked about, too. I do a lot of writing, I write stream of consciousness on giant canvases. People ask why I do it, and it’s because it looks good.”

Reflecting a band that Wilson calls “maximum folk,” though the word “psychedelic” has also been thrown around, the heart of Lee Harvey Osmond comes from the 1960s. The name references both the man who killed John F. Kennedy (too soon?) and the people who merely assassinated pop culture – the Osmonds.

Wilson explains, “When I was four years old, we had a black and white TV and it hardly got any reception. Before I remember Romper Room, and before I remember The Friendly Giant, the thing I remember the most at four years old was JFK getting killed on TV. That fear, that reality that somebody could touch something that seemed so solid in our culture, in our lives, to four-year-old, that resonated with me to this day, and since then seeing things we’d never thought would happen.”

Like the Osmonds.

“Pop culture homogenizes us from an early age: look at this shiny thing over here! It pacifies all our fears for us. That’s the way the ‘60s looked to me. It was a mixture of two different cultures: Fear culture and a shiny thing culture that made us look in the other direction. The Osmonds were the shiny thing – that and the most evil fucking creature on the entire planet: Mickey Mouse.”

The band naming could’ve gone another direction.

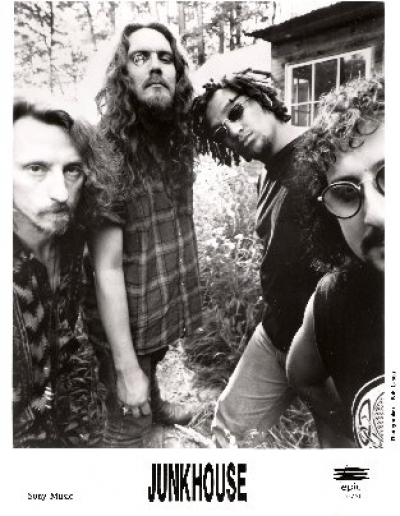

The 56-year-old singer songwriter’s other bands (and their names) also reveal a depth of character and talent. He first turned up as the hairy, tough-talking, gruff-voiced frontman of Junkhouse in 1993 with the single Out of My Head – both song and aptly named band speaking to the mean streets of working class Hamilton, Ontario from whence they came. It was a huge hit in Edmonton. Though the original guitarist Dan Achen died in 2010, the rest of Junkhouse assembled recently for what was thought to be just some one-off dates.

The 56-year-old singer songwriter’s other bands (and their names) also reveal a depth of character and talent. He first turned up as the hairy, tough-talking, gruff-voiced frontman of Junkhouse in 1993 with the single Out of My Head – both song and aptly named band speaking to the mean streets of working class Hamilton, Ontario from whence they came. It was a huge hit in Edmonton. Though the original guitarist Dan Achen died in 2010, the rest of Junkhouse assembled recently for what was thought to be just some one-off dates.

“It was crazy,” Wilson reports. “I say this was not out of ego but of complete fucking surprise. We had 9,000 people turn up to see us in where the hell were we, Welland, Ontario, at a festival in a parking lot. I play music every week of my life, so it’s not like I don’t know what’s going on out there, but holy shit, I was surprised.”

So don’t rule out a Junkhouse reunion.

The next chapter in Wilson’s career was unexpected to people who didn’t think the Hamiltonian biker man yarling about being out of his head would be capable of sensitivity – but he was! The costumed folk trio Blackie and the Rodeo Kings, which also featured Canadian rootsmen Stephen Fearing and Colin Linden, was started as a tribute to their mutual hero Willie P. Bennett, and in fact the band often close shows with his song White Line. Blackie has since become a staple on the folk circuit. Wilson has long been a fan of storytelling style songs that can be played at one’s kitchen table with “a pot of coffee and a pack of smokes,” so this wasn’t just a case of a rock guy softening up with age.

And now comes Lee Harvey Osmond, which sounds like the love child of Tom Waits and Leonard Cohen with producer Mitchell Froom as their gynecologist. In 2009, the band released its debut album A Quiet Evil – another fitting name given its bohemian, psychedelic sound. Maximum folk.

Wilson says he doesn’t have much in common with his folk festish peers, “Traditional folk with the fiddley die-dohs all comes from another country. I’m a fucking Mohawk. My music comes from this land. The way I interpret my heart is through North America, so I didn’t really fit with the people with folkie beards who have weird food stuck in them. I don’t fit in with those people, and I never wanted to. But I play real folk music. Folk music to me is taking the story from my fire and bringing it to your fire in Edmonton.”

Wait, what did he say? He’s a Mohawk? It’s true. Wilson never made much of his native heritage – mainly because he never knew himself until recently. As he told CBC radio for the first time in 2014, by pure fluke a few years ago found out he’d been adopted, and raised by loving parents in Hamilton with a close cousin who wasn’t his cousin but turned out to be his birth mother. They never told him the truth, though he says he sometimes wondered why he looked different than other kids.

“I never lived that life,” Wilson says, “but now my sisters are telling me: ‘you gotta get your status!’ And I’m meeting an unbelievable amount of family I never knew I had. It’s flooring me. Our fathers were ironworkers, Indians with busy dicks.”

It’s a mind-blower to find out that who you are isn’t who you thought you were, but then you turn out to have been the same person all along and maybe better for the experience. He says never got mad at his family, quite the contrary, but it sounds like Wilson is still processing the information. Maybe it’ll come out in the novel he’s working on, to be called Beautiful Scars. It’s the same title as Lee Harvey Osmond’s latest album, and also the title of a song Wilson wrote (AFTER the album came out without its title track; he admits he’s not marketing genius). The phrase obviously means a lot to him.

He says, “Our lives are all great works of art, and along with that are beautiful scars that make it way more interesting – makes it less Osmond and more Lee Harvey, I guess you could say.”