Harpdog Brown gets real

Posted on May 12, 2016 By Mike Ross Entertainment, Front Slider, life, Music

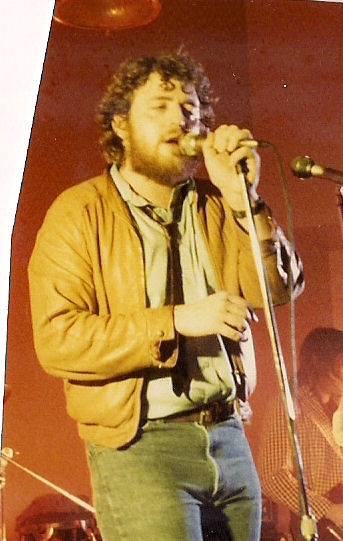

If Harpdog Brown has been faking it all these years, he deserves an Oscar – in addition to his two consecutive Maple Blues Awards for the best blues harmonica player in Canada, plus the Juno nomination. He’s too convincing for it to be an affectation.

If Harpdog Brown has been faking it all these years, he deserves an Oscar – in addition to his two consecutive Maple Blues Awards for the best blues harmonica player in Canada, plus the Juno nomination. He’s too convincing for it to be an affectation.

By now, more than 35 years after he started with single-minded determination, he’s become a big deal in the Canadian blues scene.

“Dog” (only a few people know his given name) is one of the performers and producers of the “17 Years After” Blues Marathon Reunion (and its original event 17 years ago), Saturday at the NAIT Gym, with Sue Foley, Leon Blue, Amos Garrett and many more.

Some people say Harpdog is guilty of the most heinous crime of cultural appropriation, a Vanilla Ice of the blues. Along with looking the part of the archetypal blues-man, and a bit of a show off, Brown sings with unabashed swagger and twang, raspily riffing and booming through stanzas of bluesy tropes in an accent seemingly borrowed from a mythical part of the American South that doesn’t exist – though he grew up in Edmonton. He pounds home his songs with the passion of an evangelist, a street preacher. He wows his vowels, struts his lines, and hams it up to a point that stops just short of burlesque. Also, as noted, he plays a pretty mean harp. The whole package is enormously entertaining.

Brown may have adopted this character to fill a cultural void in his youth, maybe because he was in fact adopted, but he evolved into it over time. It’s who he is now.

He talks like he’s on a mission.

“I speak the blues like it’s the truth and it is the truth,” he says in a recent interview. “I do feel more like I’m a servant of the people. Music is the vehicle, but I’m in the people business. And I heal people – if they pay attention of the good messages of life that come out of the songs that I choose.”

This goes beyond the stage. The lifestyle of a traveling blues musician is itself fuel for an unending series of blues songs: loneliness, boozy nights, heartbreak. Harpdog even named his son McKinley, after blues hero Muddy Waters, aka McKinley Morganfield. The boy was born deaf (fitted at age four with a cochlear implant); he’s 19 now, doing well on his own; he even helped out dad last summer on the road in Western Canada. Harpdog is on road most of the time. Most of his many relationships have been brief, but “deep,” he says – yet more fodder for blues songs.

“I was born to travel, I was born for the circus,” he says.

Only now has Harpdog Brown started to write about his own life – as will be heard on an upcoming album called Travelin’ With the Blues. On the record is a little talkin’ blues number called What’s Your Real Name?, the annoying question he gets asked all the time. It happened in 1989: He tells of hearing some fans at a gig shout out the words “Harp dog! Harp dog!” – he’s sure it wasn’t “hot dog!” – and thought it had a good ring to it.

“So I accepted that name,” he speak-sings in the song. “A few years ago I made it legal – is that real enough for you?” He adds later, “Harp is what I play, not who I am.”

There’s a lot of untapped life material to come.

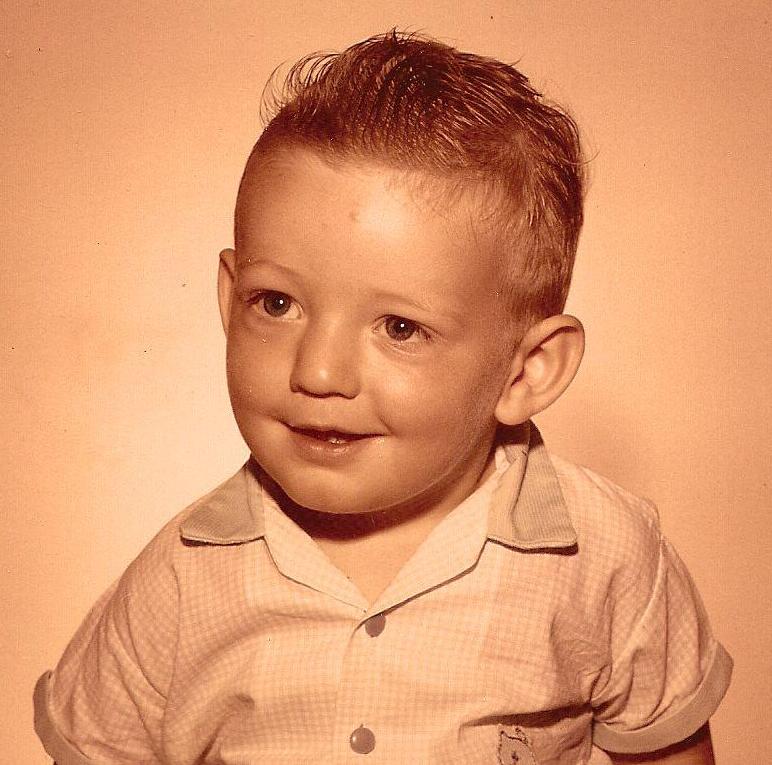

“I’m a bastard child,” says Brown, who was conceived in the back of a ’57 Chevy somewhere between Lacombe and Sylvan Lake, Alberta. His mother Mary, aged 15 and a good Catholic girl, was sent to the area nunnery to have the baby. Both of her parents tragically died while she was pregnant, and her older siblings convinced her to give up the baby for adoption. The future Harpdog was delivered by the nuns because the doctor couldn’t make it in time.

“I’m a bastard child,” says Brown, who was conceived in the back of a ’57 Chevy somewhere between Lacombe and Sylvan Lake, Alberta. His mother Mary, aged 15 and a good Catholic girl, was sent to the area nunnery to have the baby. Both of her parents tragically died while she was pregnant, and her older siblings convinced her to give up the baby for adoption. The future Harpdog was delivered by the nuns because the doctor couldn’t make it in time.

Brown only found out about all of this 29 years later, after Mary – who had moved to the UK to start a new life – spent a decade seeking him out. They first met in person when Harpdog was opening for the Downchild Blues Band in Vancouver. Spending time with his birth mom after all that time, he says, “simplified the complicated life of why I am the way I am.”

Brown says his first conscious memory was being told by his new parents that he was adopted – and it messed him up.

“It was kind of double edged sword,” he says. “I understand they didn’t want me to hear it from someone else. The way they put it is that I was chosen, I was special, the right way to do it. But in my head, I’m like, man, if you think I am your own, why are you telling me I’m not your own? It didn’t sit right. I felt like I really didn’t belong. I was loved by all, but owned by none.” It didn’t help that he didn’t have a strong father presence, nor many relations to look up to, no family history. He was a man with no culture in the vacuum of Edmonton.

Brown already had aspirations to be a traveling musician by the time he discovered his muse: the blues – or maybe the blues discovered him.

“I stumbled into the blues. I didn’t go searching for it. The blues just sort of appeared. The first blues act I saw when I was 17 years old was James Cotton at the SUB Theatre. I hadn’t even bent a note on the harmonica yet.” Later that same year he snuck in to see Dutch Mason, and the kid was hooked. He took up the harp and didn’t turn back.

He recalls, “It was really the first time I found a place where I felt like I undeniably belonged. The blues doesn’t ask you where you’re from or what colour your skin is. Let me quite Satchmo: He was the one that said cats of any colour can play this music.”

Brown’s first proper blues band was called Yesterday’s Paper, which was effectively a Blues Brothers cover band, complete with a three-piece horn section. The Blues Brothers movie had just come out and the soundtrack was a big hit, so it worked. The band’s first gig was a joke slot opening for Teenage Head at the Dinwoodie Lounge, and a proper launch at the old Ambassador Hotel when it was a blues bar – where people like James Cotton played a number of times. There followed an ill-fated tour of small-town Alberta. Brown would rather see the band break up than compromise by playing more popular pop cover tunes to please the Alberta bar crowd – and it did. Yesterday’s Paper folded five weeks after it started.

Brown’s first proper blues band was called Yesterday’s Paper, which was effectively a Blues Brothers cover band, complete with a three-piece horn section. The Blues Brothers movie had just come out and the soundtrack was a big hit, so it worked. The band’s first gig was a joke slot opening for Teenage Head at the Dinwoodie Lounge, and a proper launch at the old Ambassador Hotel when it was a blues bar – where people like James Cotton played a number of times. There followed an ill-fated tour of small-town Alberta. Brown would rather see the band break up than compromise by playing more popular pop cover tunes to please the Alberta bar crowd – and it did. Yesterday’s Paper folded five weeks after it started.

But Brown kept going with a vengeance, assembled band after band to play the blues. Solo or duo, if no band was available. He kept studying the masters and played most of the blues standards through the 1980s. There was a break. He moved to Vancouver in 1987 “with a woman I’d saved from a bad marriage” and designs on a real career and normal life. It didn’t last. Neither did the relationship.

By then Brown could really blow a good harp, so he answered an ad in the Georgia Strait and landed the role of Elwood in a Blues Brothers tribute band. He says he got fired and hired back three times in two years – for “attitude.”

It served him well. You need to have an attitude to make a living playing the blues.

But Harpdog doesn’t need the “blues hat” anymore. He doesn’t need to wear the cool shades on stage, ones he used to wear in the early days so “people couldn’t see my scared eyes.”

Travelin’ With the Blues, planned for a fall release, will be Harpdog’s fifth studio album, produced by Arkansas bluesman Little Victor, at a studio in California that used two-inch analog tape on a machine that’s been working steadily since 1954. Old school. The record sounds old school, authentic, resonating not only with impressively tooting harmonica solos, but with influences all over the blues map: Chicago, New Orleans, Memphis, a little Austin, Texas. Ten of the 14 songs are original. There are personal twists, like Facebook Mama – blues for the new age. Lotta blues on social media.

The Travelin’ Blues Show

There are deeper truths within. Sacrifice, one of the better ballads, is about life. In short, every move forward comes at a cost. For Better or Worse – written in a burst one night during an uncertain time – is about having no regrets, though Harpdog sings, “If I could go back in time, I might have changed a few lines or picked some different friends.”

Brown claims he’s not the kind of songwriter who gets too personal – “I don’t conjure. I kind of connect with the muse and the song just kind of flows through me, I’m not overthinking it,” he says – but that may change. What’s My Real Name? is a good start.

And never forget he came from Edmonton – he calls it the “Big Onion” in his song of the same name – where so many creative types have created their own culture.

“Yeah,” Harpdog says, and laughs. “Edmonton gave me the blues.”

One Response to Harpdog Brown gets real