Sigmund Freud dissects the joke

Posted on October 2, 2016 By Mike Ross Comedy, Entertainment, Front Slider, literature, Science

In Sigmund Freud’s 1905 book Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious, the father of modern psychiatry claimed there are only seven jokes that have ever been written – and that includes dick jokes.

In Sigmund Freud’s 1905 book Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious, the father of modern psychiatry claimed there are only seven jokes that have ever been written – and that includes dick jokes.

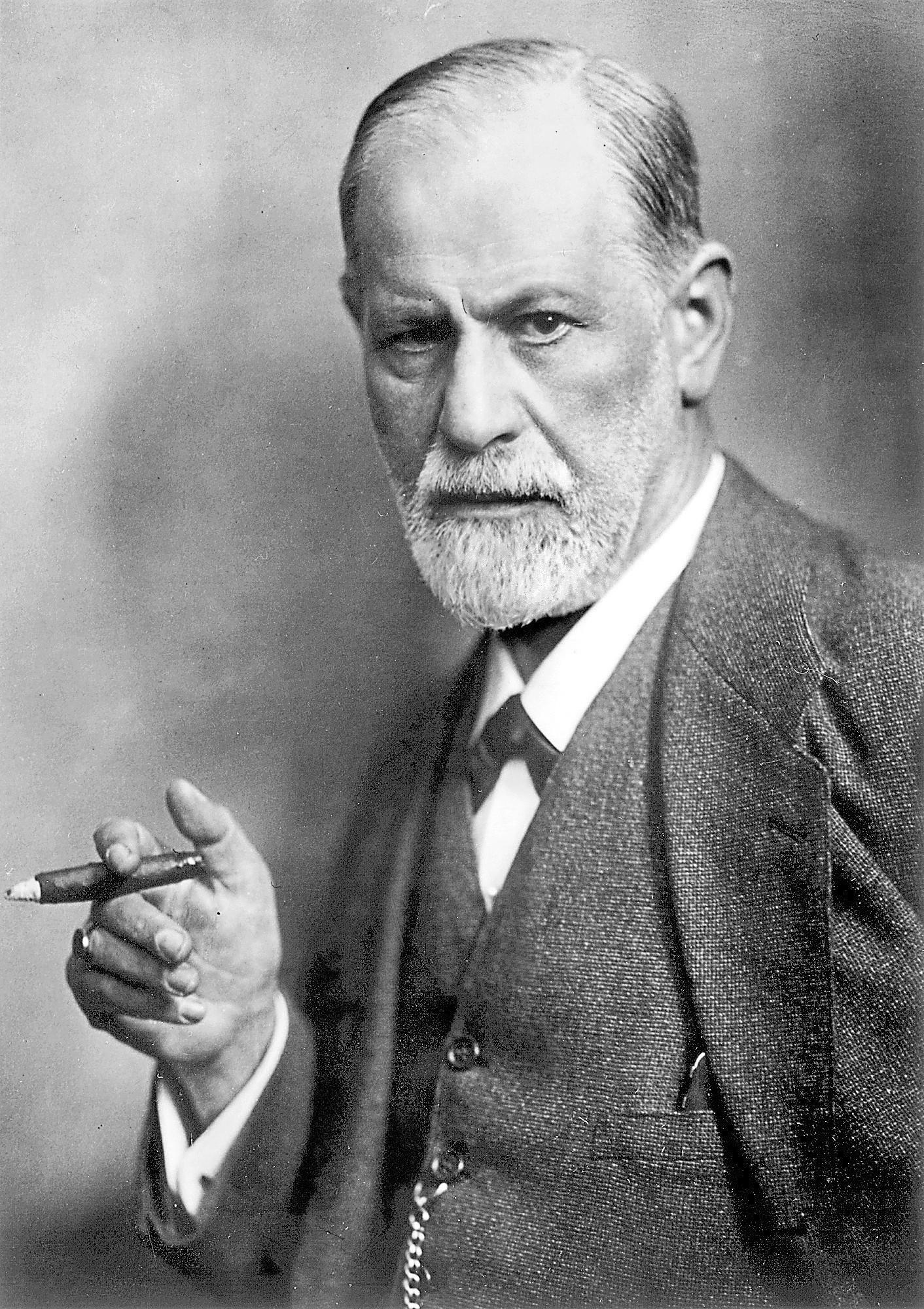

Hey, it’s Freud.

Of course he meant there are seven types of wit. The popular interpretation boils down to these: Absurdity, allusion, comparison, exaggeration, faulty thinking, word-play and reproach. There’s lots of overlap.

Stand-up comic and 630 CHED host Andrew Grose brought up Freud’s Seven Jokes recently, leading up to the Edmonton Comedy Festival Oct. 5-8, which he produces.

“Freud nailed this,” says Grose. “He absolutely did understand the comic’s mind. Take any joke you’ve ever heard and find a joke that doesn’t fit one of those categories – there aren’t any.”

As an example, headliner Tom Arnold has been called the human punchline. “It’s pretty lonely and sad to be single,” one of his bits goes. “Every night was the same for me: I’d go home and curl up in bed with my favorite book. Well, actually it was a magazine.”

Here we see an example of analogy (the magazine as a symbol for masturbation) combined with that pillar of modern comedy, self-reproach.

Arnold also talks about his wife and family (and ex-wives) in what Freud calls “tendency wit,” which requires three people to function: The joke teller, the joke listener and the usually unwitting subject of the joke. There’s a lot of this in modern comedy, too. Many of these witticisms serve to vent hostility, challenge authority, or rebel against sexual repression – and we’re back to dick jokes.

Arnold let loose on his ex-wife Roseanne as a “surprise” guest at her comedy roast in 2012: “I’ve got Rosie’s face tattooed on my chest, and believe me, it is hard to get a woman to have sex with you when Roseanne is staring at you – it’s even harder to masturbate.” Roseanne retorted later, “I’d like to thank Tom Arnold for showing up tonight, it was very brave, and he was very funny. But Jesus Christ! How many jobs do I have to get for that guy?” Allusion. She gave him his start in show business. They’re still friends.

Another comedy fest headliner John Wing also has a good line about marriage: “Marriage is a learning experience – for men. For women, it’s more of a teaching experience.” This is reproach against an entire gender.

Marriage was apparently a different game in Freud’s day, at least among the upper classes of Vienna, Austria where he hung out. He relates a witty jest of the time: “On being introduced to his prospective bride the suitor was rather unpleasantly surprised, and drawing aside the marriage agent he reproachfully whispered to him, ‘Why have you brought me here? She is ugly and old, she squints, has bad teeth and bleary eyes.’ ‘You can talk louder,’ interrupted the agent. ‘She is deaf, too.’”

Marriage was apparently a different game in Freud’s day, at least among the upper classes of Vienna, Austria where he hung out. He relates a witty jest of the time: “On being introduced to his prospective bride the suitor was rather unpleasantly surprised, and drawing aside the marriage agent he reproachfully whispered to him, ‘Why have you brought me here? She is ugly and old, she squints, has bad teeth and bleary eyes.’ ‘You can talk louder,’ interrupted the agent. ‘She is deaf, too.’”

This, Freud says, is an example of the comedy of faulty thinking.

He talks about obscene jokes, too, and while there are almost no good examples in the book (I checked carefully; just one that refers to masturbation: “It is remarkable what mortal hands can accomplish”), he adds a comment that might seem surprising coming at least 60 years before feminism, “Whoever laughs at a smutty joke does the same as a spectator who laughs at a sexual aggression.” Moreover, “A person who gives origin to such wit conceals a desire to exhibit.” Dirty comics take note.

Freud uses racist jokes to illustrate other techniques. Exaggeration is demonstrated by this: “Two Jews were conversing about bathing. ‘I take a bath once a year,’ said one, ‘whether I need one or not.’” And later, allusion again: “Two Jews in front of a bathhouse. One sighs, ‘Another year has passed by already.’”

Freud was Jewish. He says the best Jew jokes are written by Jews, and that his people practically invented self-criticism in comedy. “I do not know whether one often finds a people that makes merry so unreservedly over its own shortcomings,” he writes.

Absurdity, “the pleasure in nonsense,” is so abundant you can find it in almost every joke ever written. Legends of absurd comedy include Dudley Moore, the Monty Pythons, Andy Kaufman, Steven Wright and Reggie Watts; George Carlin, too, though he was known more of as a master of wordplay for his exhaustive deconstructions of English idiom, including the famous Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television. Almost every comic knows the pleasure in nonsense. Tom Arnold has a line, “Any time your head explodes, that’s not a good situation,” because clearly one’s head does not literally explode. That would be absurd.

Absurdity, “the pleasure in nonsense,” is so abundant you can find it in almost every joke ever written. Legends of absurd comedy include Dudley Moore, the Monty Pythons, Andy Kaufman, Steven Wright and Reggie Watts; George Carlin, too, though he was known more of as a master of wordplay for his exhaustive deconstructions of English idiom, including the famous Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television. Almost every comic knows the pleasure in nonsense. Tom Arnold has a line, “Any time your head explodes, that’s not a good situation,” because clearly one’s head does not literally explode. That would be absurd.

Nonsense can also be used to ridicule the stupidity of another. Grose comes up with a fresh punchline off the top of his head during our recent interview. I feed him an absurd set-up: “Mayor Don Iveson is a robot,” and he adds the kicker, “I’m surprised he got built on time.” It’s the birth of a joke! It needs work, and whether it’s funny or not depends on how you feel about the Mayor, Grose says, but it will serve as an example.

As for puns and wordplay, “We have perhaps been influenced by the low estimate in which this form of wit is held,” Freud writes, but he says such simple techniques are prime sources of pleasure in wit. Most wordplay jokes are “harmless” jokes, as opposed to tendency wit, and only require two people to work. His example is another Jewish joke that’s survived the years, again with the baths: “Two Jews meet near a bathing establishment. ‘Have you taken a bath?’ asked one. ‘How is that?’ replies the other. ‘Is one missing?’”

Freud explains, “Obviously the technique lies in the double meaning of the word ‘take.’ In the first case the word is used in a colorless idiomatic sense, while in the second the verb is used in its full meaning.” Result: laugh. Maybe. Freud subjects several jests to this sort of “reduction,” meant to boil all the humour out of them to see what technique is used to make them funny, if they even are funny.

Comedy in allusion and comparison can be especially fleeting, Freud says. This joke: “This girl reminds me of Dreyfus, the army does not believe in her innocence” must’ve been hilarious when French army officer Alfred Dreyfus was on trial for treason in 1894. Freud says, “Witticisms can lose their pleasurable effect over time, being tied to persons or events in an actual time.” He adds, “The many irresistible jokes about our present war will sink in our estimation in very short time.”

As will the Don Iveson robot witticism (absurdity plus reproach and allusion), where you’d have to know that Edmonton seems to be having a problem finishing large projects on time. Also our mayor doesn’t show any obvious signs of being a robot; that would be absurd. Already the joke isn’t funny anymore.

Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious isn’t a funny book, per se, but in addition to the author’s thorough and fascinating examination of why and how humans find pleasure in humour, there are a few possibly unintentional jests. Explaining that brevity is wit, Freud says, “By applying the process of reduction, which aims to cause a retrogression in the particular process of condensation, we find also that the wit depends only upon the verbal expression which was produced by the process of condensation.”

Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious isn’t a funny book, per se, but in addition to the author’s thorough and fascinating examination of why and how humans find pleasure in humour, there are a few possibly unintentional jests. Explaining that brevity is wit, Freud says, “By applying the process of reduction, which aims to cause a retrogression in the particular process of condensation, we find also that the wit depends only upon the verbal expression which was produced by the process of condensation.”

What does all of this mean? All you have to know is that wit leads to the truth. Carlin said that language is by and large a way of concealing the truth – but he was joking. Truth is the basis of all comedy, says Andrew Grose, who’s been doing stand-up comedy for more than 25 years and is a dedicated student of comedy.

On the pleasure in voicing forbidden thoughts, Freud says, “Everyone who allows the truth to escape his lips in an unguarded moment is really relieved to have rid himself from this thought.”

Not without consequence. Earlier in the book you can read a line from the 18th Century (from German scientist-satirist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, who sounds like a funny guy who had some missing e’s in his name): “It is almost impossible to carry the torch of truth through a crowd without singeing someone’s beard.”

It still stands up 250 years later – using almost all the techniques of a solid joke. It’s even funnier now that beards are all the rage again.